Why are fertility levels declining in India? | Explained Premium

Why are fertility levels declining in India? | Explained Premium

The story so far: A comprehensive demographic analysis of global fertility in 204 countries and territories from 1950-2021 has found that fertility is declining globally and that future fertility rates will continue to decline worldwide, remaining low even under successful implementations of pro-natal policies.

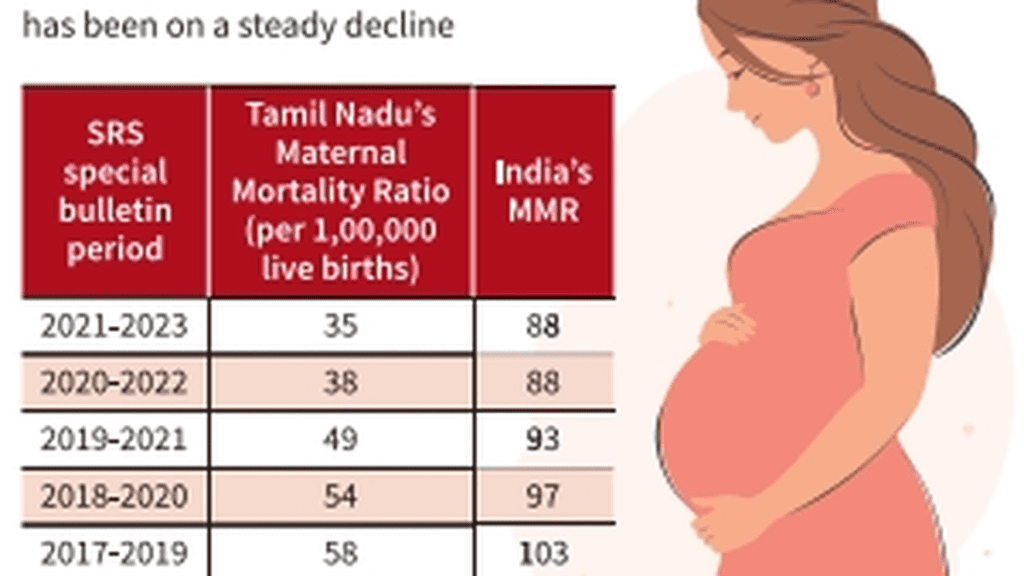

The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2021, noted that India has moved from a fertility rate of 6.18 in the 1950s to a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 1.9 in 2021. This, it pointed out, was below the replacement fertility level of 2.1 (which is the average number of children a woman should have to replace herself and her generation, for population stability). The GBD study projected that the TFR could fall further to 1.04 — barely one child per woman — by 2100.

The steep fall in fertility levels has triggered concerns about the political and socio-economic fallout, especially in the southern States, which fear the loss of parliamentary seats post the delimitation exercise in 2026.

Even though the country has had one of the oldest birth control/family planning programmes, increased female literacy, workforce participation of women, women’s empowerment and improved aspirations could have contributed more to the steady drop in fertility rates over the decades than the faithful adoption of family planning initiatives.

The decline in fertility rate has also a lot to do with changing societal attitudes towards marriage and reproduction, with women increasingly exercising their choice. They often prefer to marry late or not at all, often choosing career and financial independence over motherhood. Rising rates of infertility in both men and women and abortions are important factors which could be contributing to this decline in fertility though no absolute data is available. With an increasing number of young men and women opting to go abroad for higher studies and jobs and choosing to settle down and raise their families there, migration is another key factor that could be in play when one considers the decline in fertility levels.

Also Read | India may face economic trouble as fertility levels drop

Declining fertility rates have resulted in a rapid demographic transition in many southern States. The consequences of this — an ageing population, a declining young workforce and increased demands on healthcare and social security measures for the care of an increasing population of the elderly — are being acutely felt in States such as Kerala. Migration of youngsters in search of better prospects is also an issue.

There is concern over the irreversible fertility decline across the country, but more so in the southern States, where fertility rates had dropped below the replacement levels much earlier than the rest of India.

Kerala led the demographic transition in the South, achieving the replacement level fertility rate in 1988, with the other four States achieving this by mid-2000. Along with education and women’s empowerment and development in the social and health sectors, which were the hallmark of Kerala’s high human development index, the State has also seen low economic investments and growth. Educated youth are leaving the State; the proportion of the aged population is expected to surpass that of children (23% in 2036). Changed attitudes towards marriage and motherhood are beginning to reflect in the health of women, leading to an increasing proportion of older mothers and pregnancy-related morbidities.

Kerala’s high labour wages and high quality of life index are attracting internal migration from other States to supplant a shrinking workforce. The State Planning Board reckons that by 2030, the proportion of migrant labour could be close to 60 lakh, about one-sixth of the State’s population.

Fertility levels drop below one in many Asian nations: Data

Fertility decline is almost always irreversible and the graph, once it starts going down, may never bounce back. Countries like South Korea, which tried to stem the demographic crisis by pumping in millions have failed and the fertility rate plunged from 0.78 in 2022 to 0.73 in 2023.

Demographers suggest that socio-economic policies that propel the growth of the economy, improve job prospects for the youth and tap the potential of a growing population of senior citizens, can help in reducing the impact of a long spell of low, sub-replacement level fertility rates on countries.