Rising temperatures link with rising dengue, researchers build early warning system

Rising temperatures link with rising dengue, researchers build early warning system

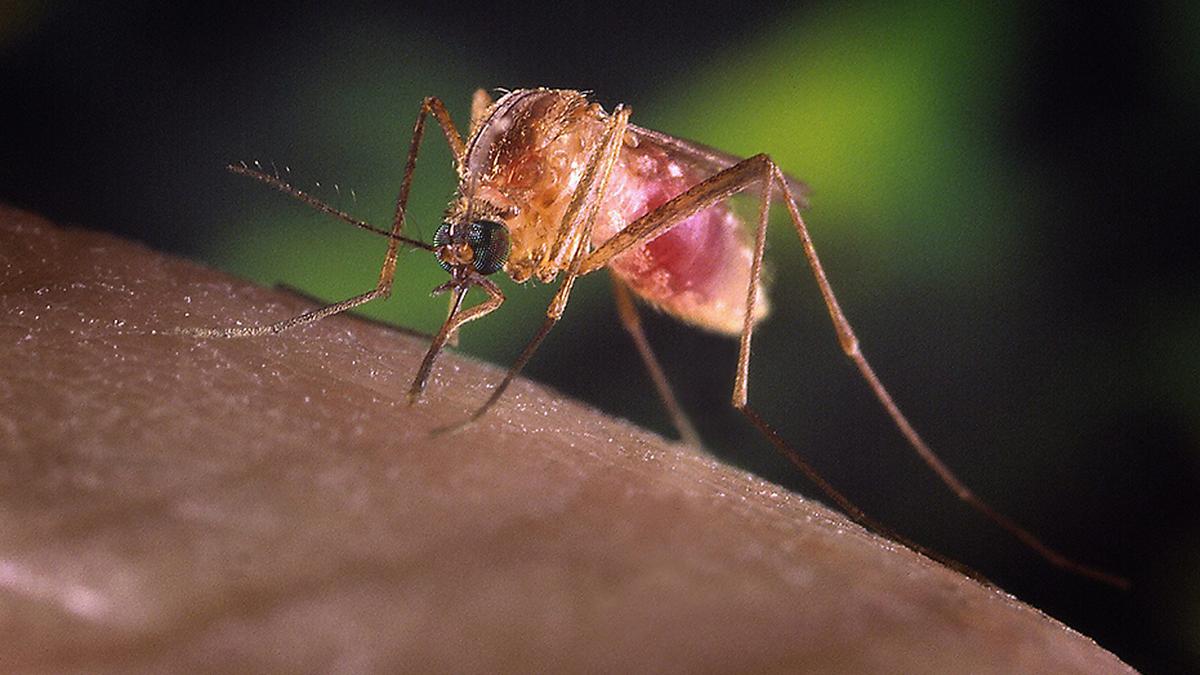

A latest study reveals that a combination of warm temperatures above 27 degrees Celsius, moderate and evenly distributed rainfall, and humidity levels between 60% and 78% during the monsoon season (June–September) increases dengue incidences and deaths. Meanwhile, heavy rains above 150 mm in a week reduce the dengue prevalence by flushing out the mosquito eggs and larvae.

The study is carried out by a team of researchers from Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), Pune; University of Maryland in the U.S.; University of Pune; University of Nottingham in the U.K.; and Maharashtra and Pune Health Department officials.

The study led by Sophia Yacob and Roxy Mathew Koll from IITM, titled, ‘Dengue dynamics, predictions, and future increase under changing monsoon climate in India’ is published in Scientific Reports on January 21. The study sheds light on the intricate links between climate and dengue in India and the research explores how temperature, rainfall, and humidity influence dengue in Pune, a dengue hotspot.

Globally, dengue is one of the fastest-spreading mosquito-borne diseases and it is escalating under the influence of climate change, with India contributing a third of the total. Without timely interventions, rising temperatures and fluctuating monsoon rainfall could increase dengue-related deaths by 13% by 2030 and 23–40% by 2050, the study said.

The team developed an AI/ML model (model based on artificial intelligence/machine-learning) for dengue predictions, offering more than two months of lead time for dengue outbreak preparedness. This can give adequate time for the local administration and health department to enhance preparedness and response strategies, potentially reducing dengue cases and deaths.

Sophia Yacob explained, “In Pune, the mean temperature range of 27–35 degrees Celsius during the monsoon season is ideal for increased dengue transmission. Temperature influences key mosquito factors such as lifespan, egg production, frequency of egg-laying, the time between feeding and laying eggs, the virus’s development inside the mosquito, and the time it takes for symptoms to appear in humans after infection. This temperature window is specific to Pune and may vary across regions, considering its relationship with other climatic conditions like rainfall and humidity. It is hence important to individually assess the climate-dengue relationship for each region using available health data.”

Roxy Mathew Koll said that the monsoon rainfall from June to September exhibits strong variability at sub-seasonal timescales, known as monsoon intraseasonal oscillations, characterised by active (wet) and break (dry) phases of the monsoon. Low monsoon variability – or lower number of active and break days in the monsoon – are associated with high dengue cases and deaths. Conversely, high monsoon variability – or higher number of active and break days in the monsoon – are associated with low dengue cases and deaths. “This means that years with high dengue mortality in Pune are associated with moderate rainfall distributed over time. In summary, it is not the cumulative amount of rainfall, but rather the pattern of rainfall that plays a crucial role in influencing dengue transmission in Pune,” Mr. Koll said.

In August 2024, Mr. Koll’s wife was severely affected by dengue and had to be hospitalised in the ICU. “Hospitals in Pune were overwhelmed with dengue patients, and this experience showed me that even as a climate scientist, no one is spared,” he said.

Currently, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) provides extended-range forecasts with information on the active-break cycles of the monsoon, 10-30 days in advance for the entire country. Utilising these forecasts can offer additional lead time for dengue predictions. Thus, monsoon intraseasonal oscillations could serve as a valuable predictor for dengue, enhancing forecasting accuracy.

The current health bulletin published by IMD provides warning based solely on a generic transmission window of temperature conducive to the development of dengue and overlooks the role of other factors such as rainfall and humidity, and the interplay with these climate factors.

Ms. Yacob said that the new study has developed a dengue early warning system that incorporates all potential climate-based dengue factors (predictors) and their combined interactions with dengue at a regional scale. “Using observed temperature, rainfall, and humidity patterns, the dengue model is able to predict potential dengue outbreaks by more than two months in advance, with reasonable skill. Such dengue early warning systems can help authorities take proactive measures to prevent and manage outbreaks, she said.

“We were able to conduct this study and prepare an early warning system using health data shared by Pune’s health department. We approached Kerala and other states where dengue cases are high, but health departments there did not cooperate. We have meteorological data readily available from the IMD. If health data is shared, we can prepare customised early warning systems for climate sensitive diseases like dengue, malaria, and chikungunya for each city or district in India. Cooperation from health departments is key to saving lives,” Mr. Koll emphasised.

States like Kerala, Maharashtra, West Bengal, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Punjab, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh, which bear a significant dengue burden, can greatly benefit from an advanced early warning system like this to enhance preparedness and reduce the disease’s impact.

The insights from this study could guide policymakers in formulating targeted interventions and resource allocation strategies for managing climate-sensitive diseases.

Sujata Saunik, Chief Secretary, Government of Maharashtra, said, “This collaboration highlights the importance of bringing together expertise from diverse fields to address complex climate-health challenges. It is a perfect example of how scientists, the health department, and the government can work together to improve our health warning system.”

Temperature and humidity over India are projected to increase further into the future, while the monsoon rainfall patterns will be getting more erratic, dashed with heavy-to-extreme rains.

Though heavy rains can wash out mosquito larvae, the model shows that the overall increase in warmer days is dominating the future changes in dengue. Under low-to-high fossil fuel emissions, Pune is expected to experience a 1.2–3.5 degree Celsius average temperature rise by the end of the century.

Dengue mortality in Pune is projected to rise across all emission pathways:

● Near-term (2020–2040): 13% increase in mortalities, corresponding to global warming crossing 1.5 degree Celsius.

● Mid-century (2040–2060): 25–40% rise in mortalities, at 2 degree Celsius warming under moderate-to-high emissions.

● Late century (2081–2100): Up to 112% increase if fossil fuel emissions remain unchecked. underreported in India, revealing that the actual number of cases is 282 times higher than the reported figures.