India’s UFC dream: Rising to glory or stumbling in the spotlight?

India’s UFC dream: Rising to glory or stumbling in the spotlight?

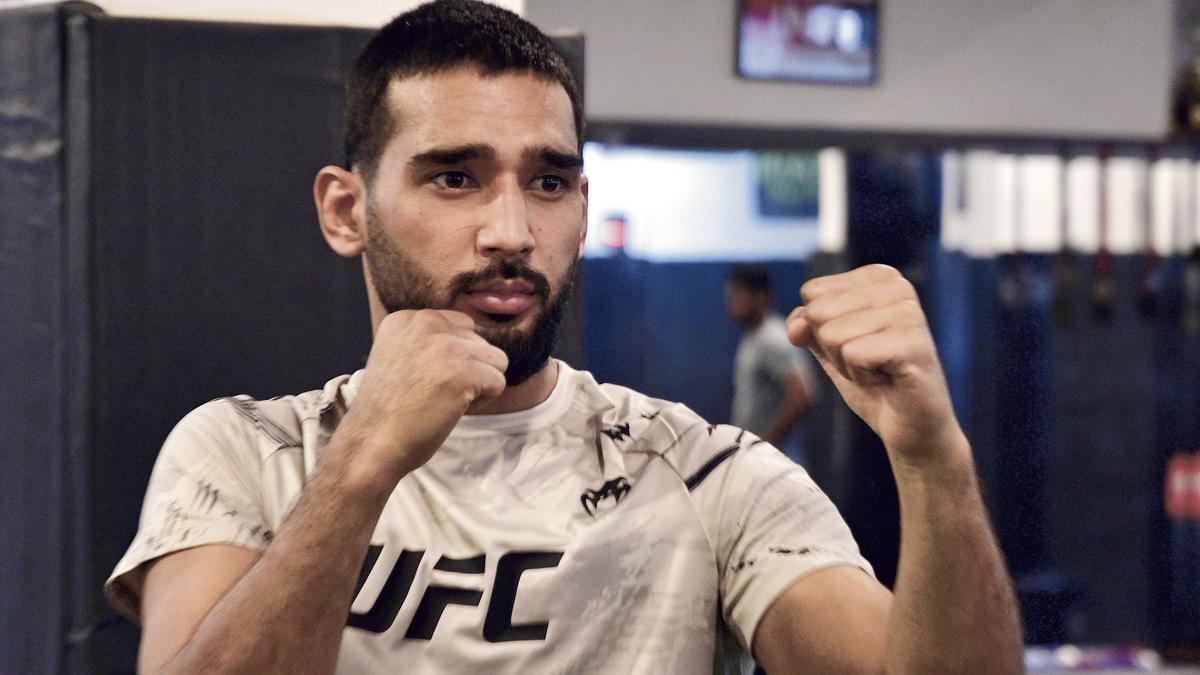

Whenever MMA fighter Anshul Jubli posts on social media these days, the responses are almost instantaneous. This quick feedback is understandable. The 30-year-old from Uttarakhand became a social media sensation a couple of years ago, amassing over a million Instagram followers after winning Road to UFC and making history as the first Indian fighter to earn a contract with the world’s premier MMA organisation, the UFC.

However, after two fights and two losses, much of the interaction on his social media is negative.

“It’s almost a guarantee what the messages will say at this point. It will be some variation of ‘19 seconds,’” says Siddharth Singh, Anshul’s coach and the founder of New Delhi’s Crosstrain Fight Club, where Anshul began his MMA career.

The “19 seconds” jab refers to the length of Anshul’s most recent UFC fight, which ended in a knockout loss to Australia’s Quillan Salkilld at UFC 312 in February. Some of the mockery has been overtly racist, while an out-of-context quote from Anshul — where he said he had to believe he could beat all-time great Khabib Nurmagomedov — has also been used to ridicule Indian fighting talent.

While Anshul bears much of the criticism, he’s not the only Indian fighter to struggle on the international stage in recent months. In March, Puja Tomar — the only Indian fighter to have won a bout in the UFC — submitted by armbar in her second fight at UFC.

The performance of other Indian fighters in various promotions is equally disheartening. Ritu Phogat, perhaps the most accomplished Indian wrestler (a Under-23 Worlds silver medallist) to transition into MMA, suffered her third straight loss at ONE Championship, submitting to a kneebar by Ayaka Miura. This marked Ritu’s first fight after a two-year layoff, and her future in the sport now appears uncertain. In December of last year, five Indian fighters competed at Brave CF 92 in a series of matches billed as “India vs Pakistan” — and lost all of them.

As Indian fighters increasingly compete in some of the biggest international promotions, many are questioning whether this is the kind of representation the country needs.

Somesh Kamra, UFC panelist at Sony Sports India and talent scout for the UFC in Asia, is one of them. “Until about two years ago, I was very optimistic about Indian fighters going in the right direction. But as somebody who’s developing the market for a major promotion, I’m actually very, very disappointed with where we are right now,” he says.

“There was a wave, maybe a decade ago, when Indian fighters were encouraged to fight at the international level, but with the expectation that they would provide an easy opponent for others. I think in the last one and a half years, I’m seeing something similar happening,” he continues. “They go there with the expectation that they’re going to lose. That’s because their managers convince them it’s a good opportunity, and that even if they aren’t ready, they will at least get the stamp of having competed at a major promotion. So they go there and lose. They might make USD 10,000 for their effort. But what it does is it creates a reputation for the fighters in India. People think Dagestani fighters are so tough because the fighters from that region who have competed internationally set a really high benchmark. That’s not what we’re seeing in India,” he explains.

While Somesh is clear that Anshul wasn’t one of those who didn’t deserve to fight at the international level — he considers Anshul’s win at the 2023 Road to UFC one of the high points of Indian MMA — he points out that matchmakers are struggling to find suitable opponents for him. “I was talking to UFC matchmaker Sean Shelby, and he was honestly struggling to decide where to place Anshul. He faced a 38-year-old grappler (Mike Breeden) who was going to be cut by the UFC, and he got knocked out. He faced a newcomer from the Dana White Contender Series (Quillan) and got knocked out in 19 seconds. So Sean, as a UFC matchmaker, was honestly not sure where he would place him,” Somesh says.

While Anshul was at least a legitimate winner at Road to UFC, Indian fighters have made headlines for all the wrong reasons in subsequent seasons. Last year’s Road to UFC saw allegations — later proven true — that Indian fighters had padded their records. This year, Chungreng Koren, considered one of India’s best fighters, had to be pulled from the competition after he wasn’t released from his contract by MFN, India’s premier promotion, where he holds the lightweight championship.

“We’re seeing a situation where, on one hand, some fighters are deciding to step up to a level of competition they aren’t really ready for, and at the same time, some of the best Indian fighters, for different reasons, aren’t getting the chance to step up at the right stage of their careers,” Somesh says.

While other observers agree with Somesh’s points, they add that it’s unfair to judge Indian MMA by the standards of regions where the sport is far more developed. “We have to understand that MMA is still in a very nascent stage in India compared to the USA, where the sport has been around for over a quarter of a century. (For perspective, UFC 1 was held in the USA in 1993, while the Super Fight League — India’s first televised MMA promotion — launched nearly 20 years later in 2012.) There’s a whole generation of fighters who have already fought and made careers in MMA in places that we consider strong in the sport. We have Anshul and Puja, but they have hundreds of people who started doing this 10-15 years ago,” says Peeyush Pandey, one of India’s youngest MMA coaches at 28, who runs Kaizen Academy in Bengaluru.

“MMA in the USA can be considered a sports industry. Right now, there is an MMA scene in India. It’s not an industry. It’s mostly driven by passion. It’s not entirely professional in terms of promotions, fighters, and coaching,” says Shillong-based MMA podcaster and commentator Andrew Lu. Crosstrain founder Siddharth shares a similar view. “What is holding us back is the lack of a big and solid ecosystem where our homegrown athletes have access to the right platforms, the right places to train, the right coaching, the right amateur tournaments to compete in, and the financial support at the right time in their development. We are much better placed than we were a few years ago, but we aren’t there yet,” he admits.

Roshan Mainam, a fighter who has competed at One Championship, adds that only a small proportion of Indian fighters come with skill sets that translate well into mixed martial arts. “One of the major issues I’ve seen with Indian fighters is that most of us lack a strong wrestling background. If you look at any of the elite international fighters, they usually have a very strong wrestling base. Most of India’s top MMA fighters come from a striking background. But no matter how good a striker you are, if you don’t have a solid wrestling background, you will always have the fear that the opponent will find a way to take the fight to the ground,” says Roshan, who himself competed as a freestyle wrestler in the Indian national championships before transitioning to MMA.

This isn’t to say India lacks strong martial arts traditions. It does. But the ability to combine these skills into a style that works well in MMA is still missing. “In India, we have great wrestlers, boxers, and wushu fighters. But very few people have actually combined them all together. I think a lot of this is due to how new the MMA scene is in India. A country like the USA has been able to put everything together for at least the last 25 years. We are still in the first generation of this development. Honestly, we probably have only four or five high-level MMA gyms in India. The rest of the guys are, kind of, winging it. The academies and coaching need to catch up before we can say we should be rubbing shoulders with the best in the world,” says Peeyush.

Even with the right coaching, a talented prospect will likely face another challenge: the lack of the right platform. “One of the biggest problems we face in India is the lack of an actual calendar. No one wants to train without being able to test that training in an actual fight. In the USA, you know that every weekend there’s some event or another. The UFC has one event every week, and it’s obviously the pinnacle, but there are probably a dozen regional promotions where your opponents are of a really high standard, possibly even former UFC-level fighters. That doesn’t exist in India. Our biggest promotion is Matrix Fight Night. But even they only conduct maybe three or four events each year. And not every fighter will get the chance to compete in every event. That means our best talent doesn’t get to compete as often as they should,” he explains.

Moreover, with many of the best Indian fighters locked into long contracts with MFN, there remains the possibility — as happened with Chungreng — that they might be unable to compete at the right time.

For any fighter looking to improve, the lack of quality sparring and competition means they often have no choice but to go overseas for better training. However, this comes with its own set of complications. Training abroad costs money, and at all levels of the sport, that’s in short supply.

“Even right now, it is a struggle to get the kind of support we need,” admits coach Siddharth. “I remember there was a press conference before her last fight where Puja actually said she was broke and looking for sponsors. I think there’s a distinction between what’s popular and what’s acceptable right now. MMA is popular in the sense that when there are fights coming up, Anshul is the hottest thing on the internet, and everyone wants to talk about it. But when it comes to sponsoring Anshul or Puja, sponsors will say it’s a blood sport,” he adds.

Despite Anshul’s large celebrity following on Instagram, it is understood that, despite reaching out to them for help in connecting with sponsors, he has received no response.

For India’s top fighters, this means that training isn’t just about getting better — it’s also about carefully managing limited finances. “The fact of the matter is that most Indian fighters train in Indonesia because it’s relatively affordable compared to training anywhere else,” says Siddharth. But even ‘relatively’ doesn’t make it easy. “Training in Indonesia costs about Rs 2 lakhs a month, and that’s not even including flights. If you train there for 10 months a year, that works out to around Rs 20 lakhs. And as a fighter, you get about USD 20,000 per fight. So even if you fight just once, you’re actually losing around Rs 4 lakhs. We try to manage as best we can. We compromise on flights, accommodation, and even coffee sometimes just to have enough to train. Anshul got USD 50,000 as prize money when he won Road to UFC, but after that, things have been really hard,” he says.

Despite the challenges, most observers of MMA in India remain optimistic about the future. According to Forrest Griffin, former UFC champion and current vice president of the UFC Performance Institute, success is a self-fulfilling cycle. He isn’t too concerned about the immediate lack of success of Indian fighters as long as the UFC itself attracts fans. “I think what’s most important is that the sport becomes popular in the country. Once MMA becomes popular, the rest will fall into place. It also helps if the country has a history of martial arts. I don’t know how much exposure MMA gets in India, but it’s not enough! The exposure will grow, which will improve the training, which will lead to better fighters, and this, in turn, will cause the exposure to grow. So, it will be a cycle of growth and improvement. When more kids become interested in MMA, there will be more gyms and more opportunities to train. India has a great wrestling culture, and I think that will transition to MMA quickly,” he says.

Griffin is optimistic that India can follow the developmental path of nations like China, which had a negligible presence in the UFC not long ago but now boasts a UFC champion. “I think the country they most resemble in their growth will be China — another country with a large population, whose average personal wealth grew tremendously. They’re also a country with a history and culture of martial arts,” he adds.

Even those aware of the challenges facing Indian MMA remain optimistic. “I’m actually very optimistic that we can improve the standard of coaching in the country. The best part of MMA is that you don’t need to be the highest level in your individual sport. GSP (former UFC lightweight champion Georges St-Pierre) wasn’t a top-level wrestler, boxer, or submission artist. But he was the greatest before the current era because MMA is about mixing these skills. That can be taught, rather than mastering a single skill set. One of the best MMA gyms in the world is City Kickboxing, in Auckland. Even though jiu-jitsu is crucial in MMA, neither of their founders had a background in it. They reached a high level through research and constant improvement,” Peeyush points out.

India’s fighters are evolving too. “The amateur fighters I see in India now are better than the professional fighters when I started,” admits Mainam.

New promotions are emerging, especially in the Northeast, says Lu. “There’s a lot of untapped talent coming from the Northeast. Promotions in Arunachal (Arturo) and Assam (Bidang) are doing a lot of the right things. They’re matching Indian fighters with the right opponents,” he says.

More significantly, says coach Siddharth, the average age of India’s fighters is getting younger. “If you look at the fighters currently at the international level, most are in their thirties or older (Anshul is 30, and Puja is 31). Puja was a national-level wushu fighter for nearly 10 years before her first MMA opportunity. She and Anshul were pioneers who opened doors for others, but they got their chances later than some of the fighters we have now. (Current Road To UFC contender Mridul Saikia is 27). We also have promising fighters in their teens who’ve been preparing for a career in MMA for many years,” he says.

If he ever feels discouraged, Siddharth recalls when he first started his MMA gym in Delhi two decades ago. “I left a career in finance in the UK to come back and start this. Back then, people thought I was crazy. Ninety nine per cent of the first people who came to my gym were trying to lose weight. That’s how MMA began in India. When I said I’d eventually produce a UFC fighter, my friends thought I was smoking something. But we got there. So when people criticise my fighters and say nasty things, I don’t react. It’s okay if they’re talking about ‘19 seconds’ now. Ten years ago, no one was even commenting. The fact that they’re commenting means someone’s in the UFC. We will get better, and there will be better things to talk about,” he says.